From a historical perspective, ‘The DaVinci Code’ is good fiction …

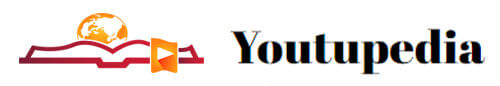

I do think the book has provided a very real cultural benefit, though. By weaving many tales of medieval Christian mysticism into its story line, the book has stimulated a multitude of readers to look beyond the veneer of printed words in search of higher meanings. This is good, because both literature and history contain them in abundance. The richness of the written word and the refining effects of time have produced works essential to our lives’ inner guidance.

Hopefully, more people will be inspired by this work of fiction to more fully explore other tomes that have even deeper meanings.

I’m referring to the Bible, the Torah, and the Koran.

Many of the world’s tensions have their roots in opinion leaders who espouse literal interpretations of those volumes. Even more preposterous is that many of these issues are fomented by their own self-serving versions of those interpretations. From the silly ‘War on Christmas’ campaign being waged by some religious conservatives in the USA to the tragic turf wars over perceived sacred grounds in the Middle East, power bases masquerading as pulpits exploit literal definitions of holy words to seek nothing more than an increase in their sphere of influence. It is not enough for them to sway likeminded individuals, they cannot wield sufficient power until they can alter the lives of those who have chosen a different moral path, no matter how independently righteous that path may be.

I believe an effective means of curbing this troubling tendency is to expose the shallowness of such literal espousings. And so, I would like to share an article written in 2000 by Rabbi H David Rose, entitled:

“The Literal Truth? Pondering the Variety of Interpretations in Scripture.”

It is one of the best dissertations on the subject that I have ever read.

The balance of today’s column consists of Rabbi Rose’s words:

“Dear God,” Donna wrote. “Last week it rained for five days straight. We thought it would be like Noah’s ark, but it wasn’t. I’m glad because you could only take two of each animal into the ark, and I have three cats.”

A professor of molecular biology wrote in a national magazine, “Given the dimensions of the ark and its wooden construction, the first stiff breeze would have broken it up. Its capacity was only a fraction of what was needed for the animals and their food supply, not to speak of their specialized needs for housing.”

Are the narratives in the Bible fact or fiction? Were the prophets truth-tellers, or great storytellers? Did Methuselah live upon this earth for 969 years, as we are taught in Genesis? Did Abraham send his first child, Ishmael, out into the wilderness and almost sacrifice his son, Isaac?

And is any of this relevant to us and to our lives?

Many who read the Bible do so in a literal way. For these people, be they Christian or Jew, the choice is simple: Either the Bible is the exact written record of God’s words, or it is not.

If it is God’s word, then it is to be followed exactly as written. If not, then why bother?

Others, including myself, are convinced that to read our sacred texts literally is to miss the point. To do so, in my opinion, is to corrupt and stagnate the ever-growing relevance of our holy texts.

The Zohar (a book of Jewish mysticism) teaches, “Were the Torah (Bible) a mere book of tales and everyday matters, we could compose a text of even greater excellence. The Torah has clothed itself in the outer garments of the world, and woe to the person who looks at the garment as being Torah.”

In other words, the essence of God’s message is hidden from a person who takes a literal view. The word is not the message; the message lies behind the words.

Consider the story of Noah’s ark. A literal interpretation misses the relevance and profound moral symbolism of the story, of the world flood and its implications for humanity.

The vital lesson of Noah’s story is the human capacity for self-destruction and the ability of one person to save the world. In our time, we possess the capability to quickly destroy creation through our nuclear power or to slowly and significantly damage our planet through waste and pollution. Like Noah’s generation, we are also able to corrupt the purpose of our existence through moral failure.

When we come to think that we or our creations are invincible, we soon find ourselves in deep water, just like the people of Noah’s generation. Even the most powerful of human beings must face their limits or be brought low.

The tale of Noah’s ark is about confronting both our power and our limitations as individuals and as society. The story is true not because it ever happened, but because it keeps on happening.

The Noah story is true, because it describes a drama we all face, generation after generation.

When we go beyond the literal sense of the text, we find meaning and relevance. When we can see our own struggles in the text, we can then take hold of the meaning of our sacred texts.

Rabbi Naftali Zvi Yehuda Berlin, an authority on the interpretation of the Hebrew Bible and a giant of 19th century Judaism, maintained that the entire Hebrew Bible “possesses the nature and the central character of poetry.” One must be aware of poetic allusions, metaphors and figurative expressions to appreciate the meaning of scripture.

How could it be any other way? Hardly a verse in the Hebrew Bible can be understood verbatim. Take the statement, “And God said.” Does God have a larynx? In what language did God speak?

To read Torah with the question, “Did it happen?” in our minds is to think of the wrong question. As Elie Wiesel has taught, “Not everything that happened is true, nor did everything that is true necessarily happen.”

We all have the capacity to recognize truth in art, in movies and in plays, whether they accurately portray something that really happened or not.

Imagine that two books are lying before us. The first book was written by a Dr. Smith, an eminent ophthalmologist. It describes a complicated surgery which restored the eyesight of a Ms. Jones.

Ms. Jones is the author of the second book. In this book, Ms. Jones reports her fright, her anxiety and her pain. Then she tells of her exultation after the bandages were removed and she could see again.

Should we ask which book is the truth? Each book has a different intention and shares a different perspective. The doctor’s truth is not that of the patient. A single criterion of truth creates needless contradictions. Both are true. Similarly, there is no single true way to read scripture.

Our sacred texts are sources of truth and meaning, and we must learn to open our eyes to them.

A literal viewing of our traditional books may obscure the truths within them, or worse, cause us to turn away and not look again.

Most of us learned scripture only as children. We were taught only literal explanations.

When we grew up, we outgrew such literal fairy tales and left them tucked away with the tooth fairy and other such nonsense.

As adults, our task in reading the treasures of our traditions and in living lives based on scripture is to uncover the layers of meaning. When we study, read and meditate on our sacred words, we discover their spritual implications.

May we hold on to our sacred texts, and may they guide our lives and give meaning to all that we do.